Sorensen Clinic

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

10 Knaresborough Place

Kensington

London SW5 0TG

United Kingdom

Appointments: +44 (0) 20 7600 4444

Email: info@sorensenclinic.com

Office hours

Monday - Friday: 09.00 - 17.30

Wallpaper* Magazine W* 133

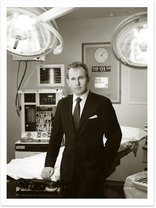

Dr Jesper Sorensen in the operating

theatre at his London clinic

Wallpaper* Magazine

'A Cut Above'

Wallpaper Director Emma Moore

interviews Dr Sorensen on his

views on aesthetics and design

Leica-wielding plastic surgeon Jesper Sorensen has transformed the tool kit of the high-precision physician.

The odds are against a physician showing polymathic tendencies these days. The intensive farming of medics - filtered by scientific achievement at an early age and incubated for seven plus years in clinical surroundings - does little to nurture the left side of the brain. Which is why plastic surgeon Dr Jesper Sørensen is such a surprise package. While there is inarguably an intensity in his dedication to his profession, as benefits a published specialist in reconstructive and rejuvenating surgery, there is more to this man than implants and uplifts. As well as running his own clinic in West London, Sørensen designs his own surgical tools and finds time to spend up to six weeks in the year on the road with a Hasselblad camera. Documenting lives in one of the world’s remotest spots.

He consults kitted out in Brioni, collects art, has a lifelong love of Italian Vogue and a collection of Wallpaper*, and might or might not have a Fritz Hansen chair or two at home. Lets just say he does have a keen eye for design, is Danish, and graduated in 1992. He is also a physician who came close, in earlier years, to becoming a photographer, and even now has a photography agent, Toronto’s Dylan Ellis Gallery.

We meet, be there any doubt, on the strength of his tool-designing credentials, not for the cut of his whistle or taste in reading matter. Not long into our meeting, he pulls out his PowerBook to show his latest project - a draft drawing of a chin implant tool he is in the process of designing for Swedish surgical supply firm Stille. It will be one of the instruments that will service a grey zone between conventional and micro-surgery, and it has all the purity of form that we expect from Scandinavian design.

Sørensen already has his name on a collection of pioneering instruments designed by the Swiss high-precision tool-makers S&T, who work exclusively by hand. Considering them superior to most, Sørensen began using S&T products while teaching micro-surgical students in Scandinavia. The company identified him as a leader in high-precision surgery and approached him to consult on development of tools. As it happened, Sørensen was already mentally reinventing the function of of his tools while in the thick of his procedures. ‘I had ideas to make one tool do several tasks’, he says. ‘To grab tissues, hold a needle, dillate a vessel. To this end I added a needle platform to the forceps.’ Another of his innovations was to extend the instruments to create better counterbalance. ‘Just because the surgery is fine dosent mean the instruments have to be small,’ he says. ‘Shorter instruments move around - if they are longer, they are better supported.’ Meanwhile, a cylindrical grip means you can turn the instrument alone without having to turn the whole hand, which compromises the precision of the action at the tip.

Sørensen’s instruments have revolutionised the business and are sought after the world over. ‘There are three ways to raise your game in the field of microsurgery - you can improve your vision, your hands, or your mind,’ says Sørensen, who always works with the best optics available, constantly educating himself by visiting other pioneering specialists and, in refining the tools of the trade, has maximised their precision and his dexterity. Not long before he began customising his tools, surgical forceps were much the same instruments that jewellers have used for centuries, versions of which you can still buy for as little as £5 in parts of Asia; something crafted by S&T costs 100 times that. ‘It’s like having a Hasselblad or a Leica - the superior results speak for themselves,’ says Sørensen.

What drives the search for even more precise instruments? Well, the greater the precision, the finer the adjustments can be. The finer the adjustments, the more natural the results. It’s not uncommon for a cosmetic surgeon to market himself on natural results, but Sørensen is particular convincing. ‘I don’t do manufactured beauty. My philosophy is that it is better to do three complementing procedures instead of one large one. Doing many small procedures with the highest possible precision - thats my secret.’

Though perhaps at odds with his professional life, Sørensen’s photographic pursuits throw an interesting light on his understanding of ‘natural’. He has long reserved a number of weeks a year for traveling in the Himalayas, documenting the lives of some of its remote inhabitants. ’I can’t do anything by halves; if I do portraiture, I want to do it really well. I focus on the natural. ‘The natural, in this case, is the faces of nomadic Himalayan tribespeople, untouched by modern artifice (or surgery), and far removed from the strictures of our youth-worshiping culture. This is a body of work celebrating untamed beauty, and a fascinating counterpoint to his work in Western medicine.

Perhaps the most interesting thing is what his two opposing passions say about beauty - that our perception of it is inextricably linked to our physical environment, artificially refined in highly constructed surrounds, and sculpted by nature in the wilds.

www.drsorensen.com; www.s-and-t.net